Over the winter I was blessed to attend a fantastic trio of ecological farmer conferences– Acres, USA; The Organic Association of Kentucky; and the Ohio Ecological Food and Farming Association; and more recently also The Real Organic Project’s symposium on the future of organic and regenerative ag and the lightning fast evolution of the use of the term “regenerative.” The upcoming Climate Smart Commodities grant has really opened up my capacity to dive into the world of agriculture-as-healthy-ecological-systems and the people who make it happen. I wanted to share some piece of what I learned with you, to bring you into the major questions which these thoughtful people are turning over (or at least incorporating into the top layer of the soil, to lead with a Plowman’s Folly joke). This is my second article working with the big themes in these movements today; the first, on the Real Roots of ‘Organic’ is here. I hope you will find useful news from the field if you are interested in this space– as a customer and eater, as a farmer, as a policy nerd or future-minded parent. Be prepared: the SEO AI overlords of google will not approve. I’m going to talk like myself and the robots will give me failing marks in keywordification and “readability” but hopefully you will not.

This Spring we find ourselves clambering into the captains perch of a grant-ship that we expect to launch this summer, which looks already to be a hot one. We will set off soon on the next five-year leg of our lifelong journey to come into community and saner farming practice with some great group of our fellow land stewards and food producers in this Ohio River Valley. Not a moment too soon of course, or too late, as everything takes its own time and as we seem to be dancing on the brink of radical transformations of major earth systems including the human-cultural ones.

In the face of this transformation, the response of the bosses bosses bosses (the bankers of the bankers) has been to introduce the financialization of nature, supposedly as a way to “internalize the externalities.” What on earth does this mean? Well, the public position of the bankers of the powers that be is that all the bad stuff of industrial capitalism– pollution, intractable poverty, addiction, traffic– hasn’t been counted on the balance sheets of the corporations, because no one was making them count that stuff, and because no one knew how to turn those things into dollar numbers anyway. Also, some good things of the earth– air, stable weather patterns, soil– were not being counted. Supposedly, if we counted up the value of these goods and bads, and built it into our price structures, capitalism would then be working to increase these goods and decrease these bads. The bad stuff is called “externalities” cause it was external to the books of the companies, and if we could put it on the books, then the companies would deal with it, internally.

Unfortunately, its not an accidental oversight that these goods and bads are not counted. These big bad problems can not be corrected in this way because industrial production of goods would absolutely not be profitable or even financially possible without paying less for raw nature (materials) than you get for finished goods. In 2006 I found the best explanation of this I have ever seen before or since, on a dusty back shelf in my college library; a book from 2000 called “The Power of the Machine” by Alf Hornborg. He’s still at it, explaining what “Ecologically Unequal Exchange” means. And while the raw nature (oil, logs, corn) is full of potential to become many things, the finished goods are just one step away from the trash heap. Similarly, industrial production of goods would not be profitable or even financially possible without spending less money in all the labor along the whole supply chain than you get out of the pile of stuff being made and moved and sold, concentrating dollars with the people who control that labor, material and the supply chain relationships between them. This is the whole point of production in our system in fact, to underpay labor and materials and thereby make profit. This is literally the definition of profit.

So if you try to charge companies to keep the earth still-whole while also extracting all the materials they need, there wouldn’t be any companies. If you tell the companies to pay a “fair” price to the makers, movers and sellers, then there wouldn’t be profitable consumer products. It would be a different set-up altogether. If you try to replace humans with robots, well, eventually, what are all those people for in this system? Point is, this system is what it is, but it is not about to be redesigned to be in the interest of “nature” and “working people” because the bankers bankers decide to put dollar values on elements which had previously not been counted. They might however, make a really nice asset bubble which they can trade on for more boatloads of money in the meantime, for as long as enough people are fooled.

Call me crazy, but this is what they are saying, not me. They made a new stock market asset class– Natural Asset Companies and had a bell-ringing party with the guys from Intrinsic Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange. They say “Nature’s Economy” is worth five quadrillion dollars! I tolled a different bell (it tolls for thee) on facebook but the algorithm made sure no one saw it. Whitney Webb and Corey Morningstar among others (but especially those two bright and intrepid ladies) have done a lot of research on the details of this story, and others which show the current variation of the general story told in The Power of the Machine.

So why on earth am I going on about this, and what does it have to do with regenerating agricultural systems? Can’t at least some of us just go back to the land and make a simple living farming and tending our land (if we can afford to get some or have it in our families)? Since the end of World War II the agricultural system has been operating as an increasingly consolidated industrial production system. Since soil was not a valued partner in this process, it is mostly dead (sterile) and/or gone (to sleep with the fishes). Now, there are physical things we can do about this. David Montgomery first wrote book called “Dirt: the erosion of civilizations” about collapse due to agricultural soil loss followed this up with “Growing a Revolution: bringing our soil back to life” about people who are learning the physical processes to put it back. This is real and possible. Humans can be the gardeners of Eden and make places better instead of worse! However, when people try to do this on a big area of land in a hurry, because we are all noticing how we are dancing on the brink of big changes, well, there are several approaches to trying to do this on a big area of land in a hurry…

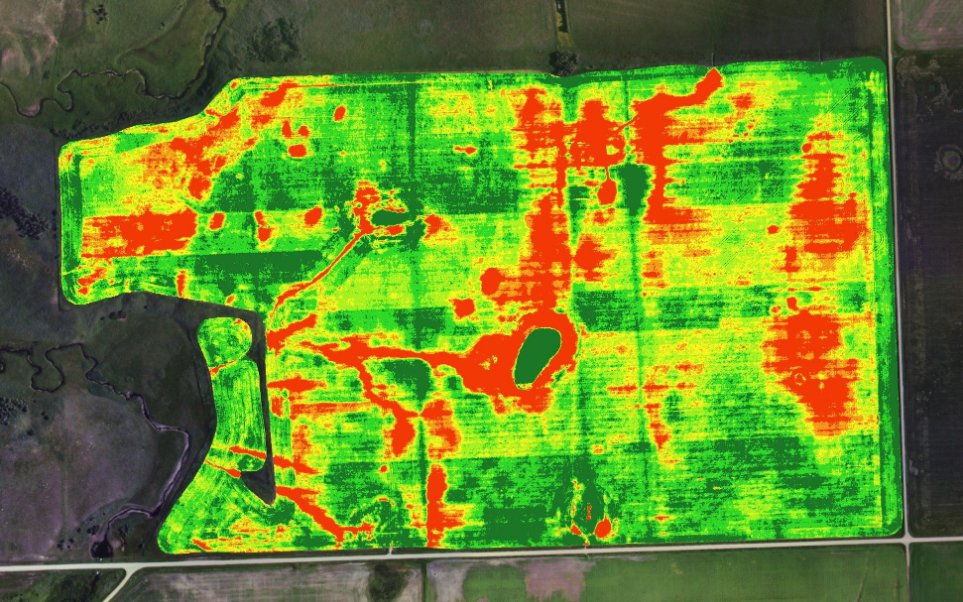

First, usually when people get in a hurry to improve a piece of land, it looks like this:

where the little house-trailer pre-school with a nice sturdy wooden ramp on the lovely shady lot next to my daughter's elementary school used to beBasically, people who are mentally adapted to the current system think that healing land is going to be a scaleable process, like all industrial processes. (White Oak Pastures has a good take on an alternative, “replicable not scaleable” at their Center for Agricultural Resilience). Need to fix those hardpan plains where we blew the tops off the mountains and packed them into the valleys to strip mine the coal? Get some recovering drug addicts (cheap labor) to plant trees on them! See, we can put the raw materials back and make the earth whole again! Cut to future picture of a bunch of dead saplings with Lynard Skynard “Needle and a Spoon” (underrated) playing in the background. Sorry, I have spent enough time on this that I don’t feel guilty saying it. Come at me in the comments. I promise it won’t be as heavy as actually caring about actual hardcore addicts. Or as heavy as seeing a forest demolished, or seeing a little peach fuzz of dying sticks on a dead lot treated as somehow future-equivalent to the forest that is gone.

To make things worse, defining the problem narrowly as “climate change” in terms of “greenhouse gases” enables the powerful people who are carefully avoiding the sharp point that industrial civilization is coming apart at the seems because it has made too many unpayable loans against the future. If the problem is “just” fossil fuels, we can use the Four E’s: Exchange Energy Sources, Emissions Management, Electrification over Combustion, Efficiency! We can get government billions for industrial megaprojects for Carbon Capture and Underground Storage. We can generate a massive mining boom for copper and other minerals; even though no amount of Green Dealing will replace the energy potential and convenience of fossil fuels, they don’t know that yet! And we can let the pesky earth-huggers fix agriculture for us, without sacrificing yield of course, our favorite measure, and they can put the carbon back in the soil and rebuild it. There, two birds with one stone: Ag Soil Carbon Sequestration.

Now I’m all for Ag Soil Carbon Sequestration. I would like for soils to be productive again. I would like to mellow the angry weather gods a bit and not burn up in the sun. I would like that for my kids (though their half-Mexican-indian skin gives them a little insurance against that particular hazard that I don’t have). In fact, I’m about to help run a five year program providing cost share, technical support, and market development for farmers who want to make their lands a bit more future-proof in a time of unstable weather and economies. We are going to cause practices to happen which will move carbon from the air to the soil through plants and animals. Looks like this is my life’s work, the work I’ve been roundabout heading towards all along.

There are issues with how permanent the soil carbon stock changes will be, with how they compare to the scale of the problem, with how hard it will be to do all this at the same time the weather patterns begin to shift more wildly than humans have seen for centuries. And these issues can be faced, but only by changing our approach to the why and the how of this work. And this brings me, finally to the question of Monitoring, Measurement, Reporting and Verification; and to a story about an ancient people in the Amazon rainforest. First the story.

There once was a jungle people who lived in the great Amazon Basin. They had some settlements, and sometimes they moved around. When they moved, they made temporary camps. When they made temporary camps, or in longer term settlements they had fires, they had latrine pits, and they had scraps from making their meals. When they left, they put the fire remains in the pits with the poop and the food scraps and they covered them. They cleaned up camp well this way. Years later, these pockets were fabulously rich places for plants, with soil microbes happily occupying the buried biochar structure from the partially burnt wood and composting all the biological materials to make fantastic “black earth,” terra preta. These people were not a people who measured their soil carbon sequestration impacts, but they lived in a way, as a regular part of their process, that generated more life. Maybe it felt right and was part of their trust in the interrelatedness of all things including their own sacred role in the community of the living, on the land that was their earth-mother.

Many years later there was another people. They trusted “the science.” They trusted “the market.” They believed that if you could measure something you could control it and they spent vast quantities of energy trying to measure things. When their world got out of whack and dying, they thought, “If only we could measure the properties of our environment which are causing this then we could figure out how to manipulate our behavior in order to shift these properties and fix the world.” They did not see that, say, running a particle accelerator about the energy used by 370,000 homes in Spain in an average year to observe the fundamental particles of matter, didn’t help them to put the quarks where they should go in order to make a harmonious functioning whole. They didn’t realize that using satellites to spy on farmers to make sure they weren’t cheating a system that paid them to plant things a little differently than they were planting things before wouldn’t actually shift the habits of their food production system in a way that would heal the land and the people. They didn’t see that shooting satellites into space to get Planet (the company)‘s “always on” imagery of “the whole world every day” to a three meter resolution wouldn’t help farmers be able to grow food in ways that increased organic matter instead of decreasing it, because it wouldn’t help all the people of the earth to live in ways, as a regular part of their life process, that would generate more life.

What if everyone’s yard was flush with tall grasses and berries and rabbits we could hunt and chickens and wild birds and root vegetables? What if this wasn’t a borderline illegal way to be on the earth? What if dogs moved about freely instead of smashing their faces against doors and fences and straining at collars? What if people turned their bodies back into the earth instead of pumping them full of anti-rotting chemicals and putting them inside plastic inside wood inside plastic inside concrete (with a drain) and then putting a little dirt on top in a little city of dead body boxes? Or burning their bodies up in a gas flame tube like a jet engine? What if our poop turned into real compost as it was among China’s Farmers of Forty Centuries or modern supporters to the shift to compost toilets, instead of into sewage slurry sprayed on hundred acre fields? What if cattle grazed like the ancient wild herds and built back prairies instead of eating corn in feedlot wastelands until they can barely walk to the slaughterhouse gate? Could you get this change by measuring soil carbon with radar from a satellite or by soil spectroscopy and comparing the changing levels with farmer practices you photograph date stamped with other satellites? Not to say that getting a lower cost way to measure soil carbon would not be useful tech, but it won’t shift the system unless new ways of considering our whole relationship with the land are welcomed to the table.

I included the following in the language of our actual grant proposal to the USDA, and I think we will be approved and funded, and that we will be odd ducks in this pool of funding, but in the pool nonetheless:

“A final statement about our approach to reporting and tracking of greenhouse gas benefits. While some parties who are primarily focused on MMRV hold the position that “if you aren’t measuring it, you aren’t doing it,” we find that this is not exactly true. In fact, for example, making and burying biochar at a steady pace but small scale will actually impact the soil and the atmosphere. Undercounting that effect will ensure that those benefits are not traded against continued emissions. Sometimes actions have consequences that you aren’t making special attention to measure. Some measures are not well-suited to influence the ongoing management decisions required of farmers. Soil organic carbon, for one, is too slow moving to inform daily practice. For this reason, we look to the decision-making and ecological observation practices promoted by holistic management. Holistic management, stewarded by Savory Institute and Holistic Management International helps farmers to observe their operations with their own senses and their own financial records and use intentional question sets to investigate their local reality and make the best decisions. This is the kind of attention to detail which allows some graziers to see organic matter and related soil carbon growing at 20x the rate predicted by the COMET-farm model. We are grateful that COMET-farm is cautious with its estimates, particularly for practices which are implemented every year, because we know that outcomes are highly variable based on management, and we don’t want those outcomes to be over-counted. At the same time, we believe that by carefully observing and tracking other visible, tactile, olfactory, and other sensory features of the land, plants, animals and fungi that we can actually achieve higher than average sequestration outcomes. We believe that higher than average sequestration outcomes for a given standard practice can be a happy byproduct of taking care of living communities. This attention to detail in ongoing management– caring diligently for young trees far beyond the date that a practice implementation is marked down as approved complete because the grower has an expectation of marketable nuts and fruits, or because she loves the creatures that will find food and habitat in the grove– is part of the value that will be embedded in our project and in our products.”

We’ll keep you posted on how our chains of values and supplies develop… Every day is an earth day (it’s where we live, after all….), though, Savory Institute and Farmer’s Footprint both have 3x match membership drives on this particular earth date.